|

Pro-Slavery Lobby

"[This is] a trade to the most advantage to this kingdom of any we drive, and as it were all profit, the first cost being little more than small matters of our own manufactures, for which we have in return, gold, elephant’s teeth, wax and negroes, the last whereof is much better than the first, being indeed the best traffic the kingdom hath, as it doth occasionally give so vast an employment to our people both by sea and land."

John Cary, Bristol merchant

|

Background

By the 18th century, slavery was seen as essential to Britain’s economy and power, and therefore accepted as the norm. The profits had given merchants and planters involved enough wealth and power to found banks and other financial institutions, and acquire immense political power. Between 1787 and 1807 all the Mayors of Liverpool were involved in the slave trade and 50 or 60 MPs represented slave plantations. They were able to build stately homes, marry into the aristocracy, and invest in industrial enterprises. William Beckford, twice Lord Mayor of London and owner of a 22,000 acre estate in Jamaica, left his son one million pounds and £100,000 a year in his will.

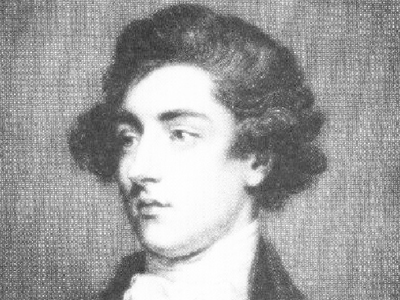

|  William Beckford by Sir Joshua Reynolds, engraved by T.A. Dean

| |

The trade helped strengthen Britain’s domestic economy, with 150,000 guns each year being exported to Africa from Birmingham alone. As well as making a fortune in the trading of Africans, Birmingham also dominated copper manufacture, as this metal was highly valued by Africans and was used for trade. The custom duties on slave grown imports were an important source of government income. The Church also had plantations, for example the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel owned the Codrington estate in Barbados.

|  'A Negro Festival Drawn from Nature in the Island of St. Vincent', depicting slavery as a life of leisure, taken from the pro-slavery book

'The History of the British Colonies in the West Indies' by Bryan Edwards, 1797.

© Anti-Slavery International

| |

For 200 years supporters of the Slave Trade were successful in drowning out the voices of opposition arguing its necessity to Britain, and how taking Africans from their homeland benefited them.

‘We ought to consider whether the negroes in a well regulated plantation, under the protection of a kind master, do not enjoy as great, nay, even greater advantages than when under their own despotic governments’, claimed Liverpool merchant Michael Renwick Sergant.

African societies and cultures were attacked as being base and savage, as a justification for tearing Africans from their homes and treating them as chattel and property as opposed to fellow human beings. Africa was linked with slavery and oppression, as Europeans had witnessed Africans enslaving each other. This despite the fact that those enslaved in Africa were usually prisoners of war or victims of political or judicial punishment, and were sometimes able to marry into the “owning” family and could keep their names and identity. These were luxuries not afforded to Africans enslaved by Europeans.

|  Liverpool’s 18th century town hall

© Liverpool Town Hall

|

Narratives from the Collection

|

Test Your Knowledge

|